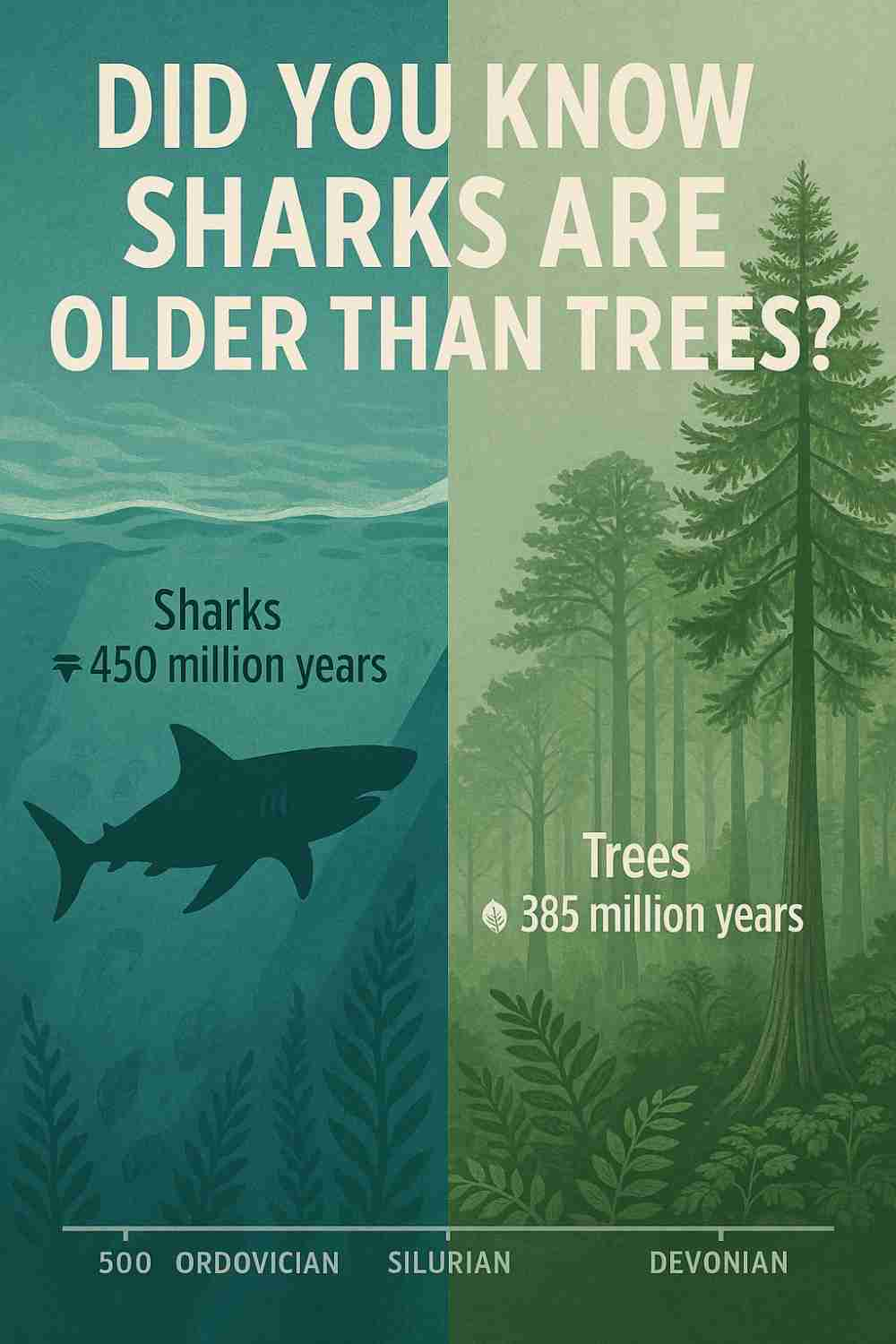

Sharks beat trees to Earth’s party. That’s the headline, and it’s true. Sharks show up in the fossil record roughly 450 million years ago. Trees—real, woody, shade-casting trees—don’t arrive until tens of millions of years later. Picture oceans full of early sharks while land was still a scruffy carpet of low plants and fungi. No forests. No leaf piles. Just ancient seas and a few brave green pioneers inching onto shore.

Sharks beat trees to Earth’s party. That’s the headline, and it’s true. Sharks show up in the fossil record roughly 450 million years ago. Trees—real, woody, shade-casting trees—don’t arrive until tens of millions of years later. Picture oceans full of early sharks while land was still a scruffy carpet of low plants and fungi. No forests. No leaf piles. Just ancient seas and a few brave green pioneers inching onto shore.

Sharks Are Older Than Trees: What “older” actually means

No single shark is older than a tree, of course. We’re talking about lineages. A family tree that keeps branching for hundreds of millions of years. Sharks belong to a group of cartilaginous fishes that appeared long before the first forests formed. Trees, as we think of them—tall trunks, true wood, deep roots—arrived later, after plants figured out how to build skyscrapers out of lignin and cellulose.

A quick timeline you can picture

Ordovician Period: the oceans fill with life; early shark relatives begin to appear.

Silurian and Devonian: sharks diversify; teeth show up everywhere in the fossil record because teeth fossilize beautifully.

Late Devonian: the first real trees rise, forests spread, and rivers change shape because roots finally hold soil together.

Carboniferous: coal swamps, dragonfly cousins with dinner-plate wings, and sharks still doing shark things.

How we even know any of this

Sharks have skeletons made of cartilage, which doesn’t fossilize as readily as bone. Teeth do. Dermal denticles—the tiny armor-like scales in shark skin—do too. Paleontologists sift through ancient sediments and find a confetti of shark teeth and denticles. Those tiny clues add up to a big story: sharks were here long before woodlands cast shade.

Trees took their time—and then they changed everything

Plants started small. Think mosses and low-slung vascular plants. Trees required engineering—tissues to lift water skyward, wood to hold a trunk aloft, roots to anchor the whole tower. Once forests spread, Earth’s atmosphere and landscapes shifted. More oxygen. Deeper soils. New habitats. Rivers began to meander instead of just rushing straight to the sea. Forests built the stage where later land animals—amphibians, reptiles, and eventually mammals—could thrive.

Sharks never left the water, and that was a smart play

Staying marine kept sharks away from the risky game of colonizing land. They refined a design that works: sleek bodies, stiff fins, replaceable teeth. Imagine an upgrade path that never stops. Lose a tooth in breakfast? Another one rolls forward like a vending machine. Many species keep several backup rows, so the “smile” is basically a conveyor belt.

Why sharks endured while so many others vanished

Earth has thrown five mass extinctions at life. Sharks took hits—sometimes big ones—but the clan persisted. How?

Generalist builds: Many species eat a wide range of prey. If one food source collapses, they pivot.

Extraordinary senses: Electroreception lets them detect faint electric fields from muscle twitches. Lateral lines feel vibrations. Smell is legendary.

Efficient physics: Cartilage keeps them light. Oil-filled livers add buoyancy. Their skin is a marvel of drag reduction—tiny tooth-like scales that cheat turbulence.

Global distribution: From shallow reefs to abyssal darkness, sharks occupy many neighborhoods. Insurance against local disasters.

“Older than trees” doesn’t mean unchanged

Sharks aren’t frozen in time. They’ve reinvented themselves again and again. Some look ancient—frilled sharks, for example—with eel-like bodies and gill frills that scream “Old School.” Others are hydrodynamic rockets. Hammerheads arrived with a bizarre head plan that seems odd until you realize it spreads their electroreceptors and boosts maneuverability. Evolution kept tinkering.

Teeth tell stories

Shark teeth are time stamps. Paleontologists can often ID species from a single tooth—the shape, serrations, and root are like a signature. Those teeth litter rock layers around the world. Entire beaches sparkle with them. And they keep rain-checks for the record: megalodon’s colossal teeth point to a super-predator that ruled millions of years ago, long after trees were common, then disappeared as oceans changed.

Trees wrote a different chapter

Early trees like Archaeopteris stitched together a brilliant set of features—woody trunks, broad leaves, sprawling roots. Forests built microclimates. They locked carbon. When vast plant matter piled up and got buried, it became coal. Without forests, Earth’s carbon story, climate, and soil would be unrecognizable. Trees weren’t first, but they were planet-level engineers.

Sharks vs. dinosaurs vs. us

Sharks predate dinosaurs by a long shot. Dinosaurs rose during the Triassic, dominated the Mesozoic, then ended with a space rock. Sharks swam before, during, and after that saga. Humans? Yesterday. Blink-of-an-eye newcomers, awed by creatures that were already “classic” when the continents had different names.

The Greenland shark and the “how old can a shark get” question

Greenland sharks grow slowly in frigid waters and can live for centuries—possibly beyond 250 years. Their pace of life is glacial. This isn’t typical for all sharks, but it shows the range. Sharks cover the spectrum from short-lived to long-lived, small to mega, coastal to deep-sea.

Misconceptions that need a quick rinse

“Sharks don’t get cancer.” They do. Biology rarely hands out total immunity.

“All sharks are apex killers.” Many are modest fish-eaters or plankton sifters. Whale sharks and basking sharks are enormous gentle filter feeders.

“Attacks are common.” Encounters are rare. Most species would rather not mess with you.

Why this fun fact matters right now

Being ancient doesn’t protect you from modern pressure. Many shark populations are declining. Overfishing, finning, bycatch, and habitat loss hit hard. Sharks reproduce slowly—fewer pups, longer gestation—so they don’t bounce back fast. The ocean needs them. Remove top predators and middle predators boom, herbivores crash, algae overruns reefs, and the whole system tips. Healthy seas usually include healthy sharks.

If you want a deep, museum-grade dive into the timeline and fossils, the Natural History Museum has a clear rundown of the evolution of sharks. For the conservation picture—what’s threatened, what’s improving, and where we need work—the IUCN keeps tabs on the global status of sharks and rays.

How to actually help

Eat seafood with a conscience. Check sustainable guides and skip endangered species.

Support marine protected areas. Safe zones give populations breathing room.

Be a picky tourist. Avoid attractions that mistreat animals or chum irresponsibly.

Speak up for science-based policies. Sharks don’t vote. You do.

The design secrets that kept sharks in the game

Modular teeth: Replace on demand. No dentist, no problem.

Hydrodynamics: Torpedo shapes, high-aspect-ratio tails, and those denticles—nature’s speed suit.

Senses turned to eleven: Smell gradients measured at parts per billion, pressure waves mapped in the dark, electric fields whispering “lunch” from meters away.

Energy math: Many sharks cruise efficiently, then sprint when it counts. The budget balances.

Trees’ counterpunch: build cities out of sunlight

Forests take light, water, and carbon dioxide and turn them into skyscrapers and food webs. Roots sculpt rivers; trunks house insects, birds, and fungi; canopies feed weather. Trees rewired the planet’s chemistry and architecture. That achievement came after sharks—but it reshaped the stage for every land creature that followed, us included.

So, who wins the “older” debate?

Sharks, by a comfortable margin. But the matchup isn’t a contest so much as a duet. Oceans refined a predator long before land learned to tower. When trees finally rose, they built the world that would one day name both players and argue about their birthdays.

A mini cheat sheet for your next dinner conversation

Sharks: ~450 million years on Earth.

Trees: later, in the Late Devonian, when forests took off.

Proof: teeth and skin denticles in ancient rocks; petrified trunks and spores on land.

Survivors: sharks persisted through mass extinctions; forests re-grew after cataclysms.

Lesson: evolution loves a good idea, refines it forever, and spreads the risk.

Parting thought

It’s humbling. Sharks patrol a blueprint that predates forests. Trees sculpt continents and air. We stroll in the afterglow of both. If that doesn’t make you feel small and lucky at the same time, try standing under a giant redwood while picturing a hammerhead sliding through blue water. Same planet. Shared history. Different calendars—both astonishing.