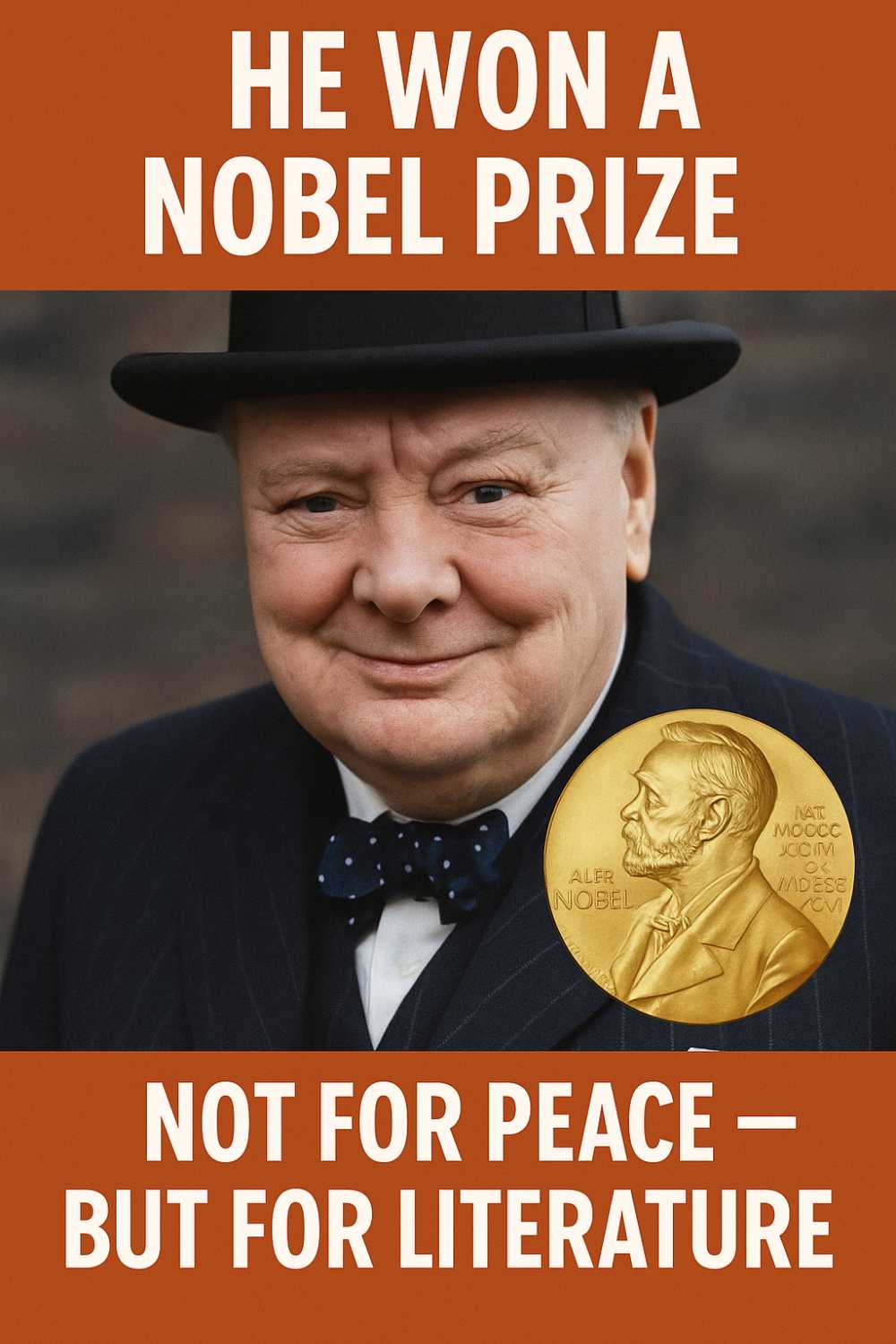

If you’ve ever heard his thunderous wartime speeches, the idea isn’t that wild. But yes—Winston Churchill, the bulldog of Britain, took home the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953. Not the Peace Prize. Literature. The Swedish Academy honored him “for his mastery of historical and biographical description” and for oratory that defended big, human values. A prime minister with a pen sharp enough to win the world’s most famous writing prize. That’s a plot twist.

Short version: Churchill wrote—a lot. He didn’t just dash off a few memoirs; he built a mountain range of books and speeches. He treated language like a weapon and a paintbrush at once. The Nobel Committee noticed.

Churchill’s Second Life: The Working Writer

Before the cigar and the V-sign became symbols, Churchill paid bills with words. He started as a young cavalry officer filing dispatches from the front—quick, vivid reportage that turned battle dust into sentences you could taste. Those early books—The Story of the Malakand Field Force, The River War—show the pattern that never left him: bold narrative, high stakes, clean verbs, and an eye for the human moment.

He kept going. Biographies. Collected speeches. Volumes of history. He didn’t plod; he thundered. He loved cadence. He built paragraphs that march. Read him aloud and you hear the drumline.

What the Nobel Really Rewarded

People often think he won “for the war memoirs.” Close, but the prize wasn’t a single-book trophy. It was a lifetime achievement nod to a body of work that blended history, biography, and a style of English that felt both grand and grounded. The committee praised the craft and the voice—especially the speeches that doubled as literature. If you want the exact wording straight from the source, here’s the official Nobel Prize citation.

The Books That Moved the Needle

The Second World War (six volumes). Not a dry staff report. It’s strategy, personality, mistakes, and momentum, delivered by the man in the room. You get cables, crises, and those midnight decisions where a comma might tip a nation.

Marlborough: His Life and Times. Four volumes on his ancestor, the 1st Duke of Marlborough. You come for battles; you stay for statecraft and the gears of power.

My Early Life. Lively, candid, often funny. It reads like the making-of reel for the later Churchill.

The River War, The World Crisis, and stacks of speeches gathered in volumes that map his thinking year by year.

These aren’t perfect histories. They’re Churchill histories—part record, part argument, all momentum. He’s persuasive, even when you disagree.

The Speeches: Prose With Boots On

Churchill grabbed English by the lapels and made it stand to attention. Short Germanic words, rolling rhythms, biblical echoes, balanced phrases. Antithesis that bites. Lists that pile up like sandbags. He didn’t write for the page alone; he wrote for the ear. Those wartime lines feel inevitable now, but they were crafted—drafted, redrafted, tested by voice, tuned like an engine.

That voice carried across the Atlantic and back again. In lonely months, it served as a backbone for millions. The Nobel Committee treated that oratory as literature, and they were right. When language holds a country together, that’s not just politics. That’s art.

So, Did He Show Up For the Medal?

Nope. December 1953, the ceremony in Stockholm went on without him. He was tied up with state business overseas. Lady Churchill accepted the honor on his behalf, and the formal words of thanks went through the usual channels. If you’d like the flavor of his acceptance, the text lives here: Churchill’s Nobel banquet speech. It’s humble, even a little cheeky. Classic Churchill.

Wasn’t He Hoping for the Peace Prize?

Privately, yes. He wanted to be remembered as a peacemaker. The irony is thick: the orator of defiance wins for literature while longing for peace. Still, the literature prize fit. He built bridges with language. He stiffened spines with syllables. His prose chased peace by steering nations through war.

Why Give a Politician a Literature Prize?

Because he wasn’t just a politician. He was a professional writer for most of his life, and he wrote with bite and beauty. Think of Julius Caesar’s commentaries—statecraft and sentence craft in the same body. Churchill sits in that narrow club where leadership and literature actually shake hands.

And remember: the Nobel in Literature has long honored historians, philosophers, and essayists, not only novelists and poets. Churchill belonged.

How He Wrote (and Wrote, and Wrote)

The myth: a lone genius pounding a typewriter at 3 a.m. The truth: a lone genius dictating at 3 a.m.—with a disciplined team. He paced, he spoke, he revised in the margins. Researchers fed him documents; secretaries kept pace; editors wrangled footnotes; Churchill hammered the sound. He obsessed over rhythm until a sentence clicked like a rifle bolt. That “Chartwell factory” didn’t dilute the voice; it amplified it.

He also understood the business side. Deadlines. Serializations. Contracts. He knew his market and wrote to be read.

Where to Start Reading Today

If you’re new to Churchill the writer:

Start with My Early Life for a lively, approachable entry point.

Dip into The Second World War with Volume 2 or 3 and see if the tempo grabs you.

Sample the war speeches in collected editions—short bursts, pure flavor.

Save Marlborough for when you want deep strategic history with narrative drive.

Tip: read a few pages aloud. That’s when his prose wakes up.

The Quibbles and the Case For Him

Critics grumble about bias. Fair. He had a strong point of view and the power to shape the archive. He isn’t a neutral camera; he’s a participant with a pen. But the prose stands. The narrative carries. Even when he’s wrong, he’s readable. And readability counts in literature. It’s the doorway to ideas.

Odd Extras That Make the Story Better

He wrote one novel, Savrola. Not a masterpiece, but a curiosity that shows his early appetite for drama.

He loved painting. Painting as a Pastime doubles as a small manifesto on creativity and mental health. He picked up a brush when the world got heavy.

The writing paid real bills. Not a side hobby. A profession.

What the Prize Means Now

It’s proof that public language matters. It’s a reminder that great writing can come from unlikely desks—war rooms, cabinet tables, late-night dictation sessions in a country house. It also shows how literature isn’t boxed into poetry and fiction. History, biography, oratory—if it’s crafted and it moves people, it belongs.

Churchill once called words “the only things which last forever.” Grand claim. But look around. His best lines still travel. The medal only confirmed what readers already knew: the man could write.